In my previous post, I wrote about various complaints and arguments that some medical professionals give regarding Spanish for healthcare courses. I explained the importance of language in healthcare and the consequences a language barrier can have on a person´s health. This week, I am addressing two more arguments: “usually Latino patients have a family member who can interpret so I do not need to learn Spanish” and “my clinic is equipped with an interpreter phone line so I can easily call and have a telephonic interpreter available.” In particular, I will discuss and compare the use of ad hoc interpreters, interpreter phone lines, professional in-clinic interpreters, and bilingual medical professionals.

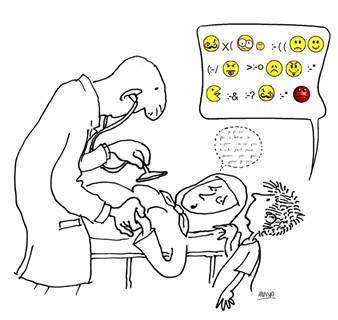

An ad hoc interpreter is an individual, typically a family member or member of the clinic staff, who is not trained in medical interpreting and who is often times self-declared bilingual or pulled away from other duties in order to interpret. Research has shown that ad hoc interpreting is currently the most widely used form of medical interpreting. Yet research has also made it evident that ad hoc interpreting can lead to poorer health outcomes. For example, Flores (2006) explains several dangers of ad hoc interpreting and gives an example of a 12 year old boy interpreting “estaba mareado, como pálido” as “Like I was like paralyzed, like something like that.” While this particular example suggests lack of knowledge or negligence, sometimes ad hoc interpreters hold a personal bias. For another anecdotal example, a social worker / interpreter in North Carolina spoke with me about a case where the doctor was explaining to a pregnant Latina about postpartum care. The pregnant woman’s husband was acting as the interpreter. When the doctor mentioned that the woman should not have sexual relations for at least six weeks after giving birth, her husband interpreted the statement as “six days.” Other studies have shown that ad hoc interpreting can decrease patient satisfaction, increase interpreting time and increase the chance that misunderstandings occur.

Another widely used form of interpreting is the use of telephonic interpreters. These interpreters typically work for a company that medical professionals can call on an as-needed basis. They tend to be well-trained and highly knowledgeable and for that reason the use of phone interpreters has provided more positive health and satisfaction results than a lower-level Spanish speaking medical professional or an ad hoc interpreter. However, the use of telphonic interpreters also has its disadvantages. For example, some studies, such as Locatis (2010), cite that the use of phone interpreters often results in shorter consults, even more so than same language visits, which raises the question of possible misunderstandings. Additionally, using an interpreter phone line implies the risk of technical problems. From a phone line going out to the physical landline needing repair, they are not 100% reliable. Another disadvantage often cited for using telephonic interpreters is the time constraint. There are times when medical professionals are in a hurry and are unable or unwilling to take the time to call. At times this is due to a medical emergency and others it is due to being behind schedule. In any case, the extra time required to call and possibly wait on hold can sometimes seem to be too much of a burden on the already tight clinic timetable. Finally, the use of a phone interpreter can limit the personal aspect of the doctor-patient encounter, which has an impact on trust and communication. Similarly, the telephonic interpreter cannot pick up on any nonverbal cues given by the patient or doctor that may clarify the speaker’s meaning. On an emotional level, the perceived “coldness” and “distance” of a remote interpreter can make receiving serious diagnosis and results more difficult. On the other hand, this last point is disputable as some research has shown the opposite: that with remote interpreters, there are fewer inaccuracies and sessions “feel more private” (Yeo, 2004). Other positive aspects of telephonic interpreters is that they are, at times, faster than using an in-clinic interpreter. Additionally, their cost and availability make the utilization of phone interpreter more accessible for smaller clinics who cannot afford to hire a staff interpreters in order to care for a small number of patients.

Lastly we have professional, in-clinic interpreters. Whether these interpreters are in-clinic staff or travel to various sites on an as-needed basis, research has shown that they are the most effective form of language mediator. Use of a well-trained, in-person interpreter significantly improves health results and patient satisfaction. Their knowledge of both the language and the culture is key to providing personal, patient-centered care. Both telephonic interpreters and in-clinic interpreters are professionals who are wonderful resources, and medical staff should be trained to work with them in order to best serve the patient. Unfortunately, many clinics clinics are unable to afford them.

However, this does not and should not diminish the need for Spanish speaking medical professionals. According to Partida (2007):

Clear communication between caregivers and patients is essential to safe, high quality health care services. Developing rapport and gaining patient trust relies on understanding. When patient and doctor do not speak the same language, there is less opportunity to develop rapport or use “small talk” to obtain a comprehensive patient history, learn relevant clinical information, or increase emotional engagement in treatment. Rather than solving these problems the introduction of an interpreter may raise another set of questions.

As stated in my previous post, language is the means by which the doctor creates rapport with the patient and learns, either directly or through small chat, about their medical history and needs. Though interpreter training programs have become quite adept at educating their interpreters in those aspects, it does not replace the benefit of direct doctor-patient communication. That is to say, as long as the doctor´s Spanish level is at the level where an adequate, meaningful conversation can take place. Another added benefit is that direct conversation saves the precious commodity of time by removing the doubled conversation that takes place as an interpreter repeats what is said. Finally, knowledge of the Spanish language promotes preventative, proactive stances to healthcare in that it prepares staff for the case where an interpreter or interpreting service is not immediately available.

Though I do not negate the benefits of professional interpreting and fully support and encourage its use and promotion, I do not believe it is a logical reason to forgo Spanish language training for healthcare professionals. As educators, we need to promote the medical staff-patient dialog while at the same time being honest with them about their language limits and encouraging the use of interpreters when needed. I hope the information I provide in this blog regarding teaching Spanish for medical professionals is helpful in meeting this goal.

RESOURCES:

BOÉRI, Julie (2012) Ad hoc interpreting at the crossways between natural, professional, novice and expert interpreting. In Amparo Jiménez Ivars and María Jesus Blasco Mayor (eds) Interpreting Brian Harris. Recent developments in natural translation and in interpreting studies. Vienne: Peter Lang. Recovered from: http://www.upf.edu/pdi/julie-boeri/_pdf/PeterLangResum.pdf

DAVID, Rand A y RHEE, Michelle (1998): The impact of language as a barrier to effective health care in an underserved urban Hispanic community. Mount Sinai School of Medicine 65 (6) 393-397.

FLORES, Glenn (2006): Language barriers to health care in the United States. The New England Journal of Medicine 355: 229-23. Recovered the 29 of November 2012, from http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp058316

KARLINER, Leah 2; JACOBS, Elizabeth A; CHEN, Alicia Hm and MUTHA, Sunita (2007): Do Professional Interpreters Improve Clinical Care for Patients with Limited English Proficiency? A Systemic Review of Literature. Health Services Research Journal. 4(2): 727-754. Recovered from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1955368/

LOCATIS, Craig et all (2010): Comparing In-Person, Video, and Telephonic Medical Interpreting. Journal of General Internal Medicine 24(4): 345-350. Recovered from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2842540/

PARTIDA, Yolanda (2007): Language barriers and the patient encounter. American Medical Association journal of ethics. (9)8:566-571. Recuperado del Virtual Mentor del American Medical Society de http://virtualmentor.ama-assn.org/2007/08/msoc1-0708.html

YEO, SeonAe (2004): Barriers and access to care. Annual Review of Nursing Research (22) 59-73. Recovered from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15368768

Pingback: Language Laws and Limited English Proficiency | Ayuda, doctor